Cardiff caves

Cardiff caves are nestled among towering beech trees with panoramic views over Cardiff’s skyline this spot exudes tranquillity. But don’t let the serene surroundings or solid ground fool you.

Beneath your feet lies one of Cardiff’s most closely-guarded secrets: an extensive network of underground caves, arguably the largest in any UK city. These caverns hold their own mysteries, from the grim discovery of a woman’s body to the calcified remains of cats.

Some secrets, like a fully equipped blacksmith’s workshop submerged under a subterranean lake, will never resurface. If you know where to look there are hints.

Rust-coloured nodules half-buried in woodland debris and disused quarry buildings cloaked in ivy offer glimpses into Cardiff’s hollow mountain. They hint at what lies beneath: a maze of unexplored tunnels, hidden chasms, bottomless pits, underground lakes, and collapsed roofs, remnants of years of mining.

The original entrance to the southern workings of the Garth Iron Mine

The original entrance to the southern workings of the Garth Iron MineNature was the first to mine this network beneath Garth Mountain on the city’s outskirts but human activity soon took over. The mountain is part of a soft, porous band of carboniferous limestone hills that delineate the southern edge of the coalfield and the northern boundary of Cardiff.

The mountain has been exploited over time by those eager to tap into the mineral wealth beneath their feet. From Neolithic cave dwellers, Iron Age Celts, early Romans, fifth-century Welsh metal workers, 16th-century iron industry pioneers, and the 19th-century Pentyrch Ironworks, the mountain has been stripped of its value. Today, Cemex, a giant Mexican cement producer, continues to operate the Lesser Garth with quarry works in Morganstown.

The Cemex dolomite quarry is so vast it makes the giant earth-moving machinery look like tiny toy trucks

The Cemex dolomite quarry is so vast it makes the giant earth-moving machinery look like tiny toy trucks(Image: industrialgwent.co.uk)

Modern-day quarrying has significantly damaged much of the Lesser Garth’s complex cave system. However the iron-working caverns in the Lesser Garth, first opened in 1565 and saved from destruction by a local campaign in the 1980s, have survived with their own macabre stories to tell.

On November 2, 1963, a group of boys exploring the iron workings mine “looking for fossils” stumbled upon the body of a young woman at the base of a shaft alongside one of the upper caverns. She had been strangled and her body discarded into the shaft from some 200ft above.

The victim was identified as Patricia Simpson, a sex worker from Cardiff Bay, and the case became one of South Wales Police’s oldest unsolved murders at the time. Despite an extensive search, her killer was never found and the case went cold until new evidence led detectives to Israel in the 1990s. A man, then in his 80s, had spent 15 years in an Israeli prison for a separate manslaughter before confessing to the murder in Wales. Despite repeated calls for his extradition to the UK for questioning South Wales Police confirmed to WalesOnline that he was never returned to Britain following his release.

The legacy of mining for iron in the Garth Mountain: hidden chasms and cavernous chambers

The legacy of mining for iron in the Garth Mountain: hidden chasms and cavernous chambers(Image: industrialgwent.co.uk)

Film director Christopher Monger, who played a pivotal role in assisting the police searches of the caverns, has deep roots in Taff’s Well, an area he knows well. Mr Monger catapulted the Garth Mountain into global fame with his 1995 film The Englishman who Went up a Hill but Came down a Mountain, a story inspired by his parents’ book. Now living in the United States Mr Monger vividly remembers the sheer scale of the caves. Speaking last year he said: “It really is hard to comprehend how enormous these caverns were. And at the next level down there were enormous lakes.”

He recalled: “The caves looked golden because the yellow ochre dust covered everything. It was astonishing. We loved going there until a murdered woman was dumped there. That stopped the good feeling.”

The allure of the caverns stretches back far beyond recent history, captivating the imagination even when they bustled with the efforts of labouring men and boys toiling in the dark. In the latter part of the 1800s it wasn’t unusual for curious tourists to embark on day trips to witness the pit workers, then under the proprietorship of a Mr TW Booker.

The tunnels inside the abandoned mine

The tunnels inside the abandoned mine(Image: industrialgwent.co.uk)

During an 1872 lecture to the Cardiff Naturalist Society Mr FG Evans described the “curious subterranean caverns”. His observations noted: “The floor is usually coated with iron ore, ochre of very good quality. The walls are lined with beautiful crystals from a speck to an inch in diameter.

“The mines amply repay the trouble of inspection. Visitors are conveyed through the tunnel in a covered carriage kept for that purpose and carry a lamp to enable them to examine the sides of the rock as they go.”

During his descent to the mine’s depths Mr Evans was captivated by a blacksmith shop hanging as if “suspended in mid-air”. Beneath him the soft glow from candles illuminated miners hard at work while blasts echoed from the rocks. Modern-day cave divers report the same blacksmith shop remains untouched, its tools still in place within the now-submerged caverns – a frozen moment from a forgotten time.

Deep inside the Lesser Garth the mountain has been hollowed out into cavernous chambers

Deep inside the Lesser Garth the mountain has been hollowed out into cavernous chambers(Image: industrialgwent.co.uk)

Adventurers and spelunkers alike remain drawn not only by the impressive iron-working caverns but also the network of caves in the vicinity. Hidden upon the Tŷ Nant pub car park in Morganstown lies the Lesser Garth Cave, known to house the exceptionally rare white cave spider Porrhomma Rosenhaueri. Also labelled Ogof Tynant, its chambers expand vastly, indicating human use throughout history.

The original entrance to the Garth Iron Mine

The original entrance to the Garth Iron Mine(Image: industrialgwent.co.uk)

Ogof Ffynnon Taf connects with these chambers, boasting nearly 400m of subterranean passageway and holding the title of the largest local cave system. Its discovery in 1986 by quarrymen unearthed skeletal cat remains, some anciently bound to the bedrock through natural calcification, preserving the feline mystery beneath the earth.

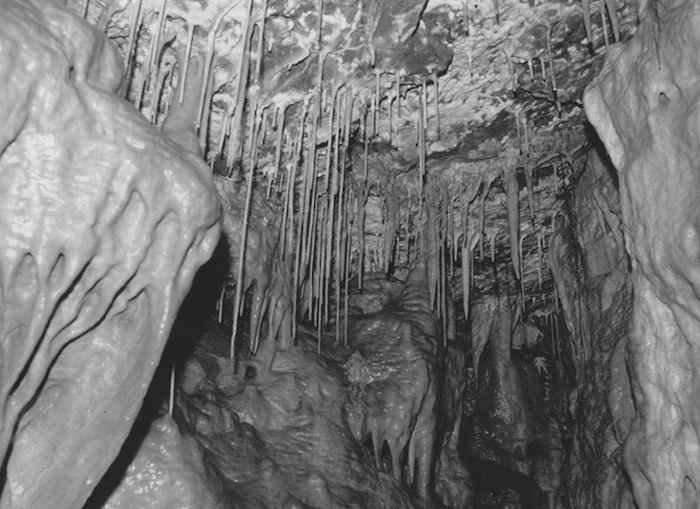

Over time the dripping water in these caves has sculpted intriguing patterns. The entrance is adorned with clusters of small fan-like curtains and magnificent stalactite pillars that stretch over 20ft long, while crystal pools lie deeper within.

Straw Grotto, inside the cavern system, where splendid stalactite pillars have grown over hundreds and thousands of years

Straw Grotto, inside the cavern system, where splendid stalactite pillars have grown over hundreds and thousands of years(Image: Garth Woods Action Committee)

Nestled within the 114-acre beech woodland it’s hard to fathom the rich history encapsulated within this modest mountain. Today the once-prevalent sound of hammers chipping away at rock underground has been replaced by the steady hum of the M4 overhead.

However, for those who know where to look, there are clear indications that the wood was not always this tranquil. This hollow mountain may still hold many secrets waiting to be unearthed.